Toby Quinn’s Online Corona Novel

Chapter 8

Brief Reply To a Hideous Critic

David Foster Wallace

Full o’ Bull

Linda, my personal assistant, just struck gold.

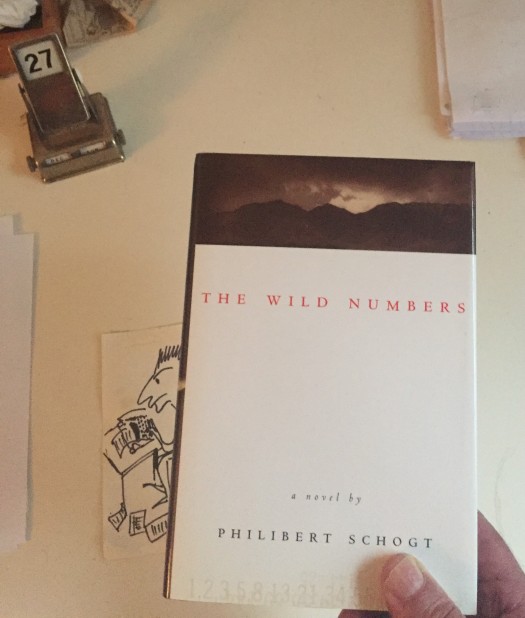

She discovered a review of Full o’ Bull’s first novel, The Wild Numbers, in an old issue of Science. That’s a damned prestigious scientific journal, right up there with Nature and The Lancet. As for the reviewer, the writer David Foster Wallace, does he even need an introduction? He was a literary genius. A spokesman of his generation. A visionary.

Do those qualifications sound at all familiar? That’s what makes Linda’s scoop doubly cool: I’ve been hailed as Wallace’s heir apparent, even as his reincarnation, albeit in a less highbrow and heavy-handed version. I didn’t make this up, folks. It’s what people are saying. And who am I to disagree?

Tragically, on September 12, 2008, Wallace, or DFW, as he is fondly remembered by his fans and in keeping with his own fondness for acronyms, lost a long battle against depression and took his own life.

Rather than weighing in on his drastic final deed with some half-baked theory, like far too many self-proclaimed psychologists who hardly knew the guy have been doing, as a fellow writer I prefer to honor my illustrious predecessor’s legacy by limiting myself to his writing, more specifically, to his review of my dear host’s fledgling novel.

“Gosh, Full o’ Bull,” I said, as I burst into the dining room, “I didn’t know The Wild Numbers had been reviewed by David Foster Wallace in Science. How cool is that!”

Wearing his chef’s apron, Full o’ Bull was at work at the dining-room table, feeding a portion of dough into his pasta maker while turning the crank. Yum!

“No comment,” he said, adjusting the knob to a finer setting before once again feeding the dough through the opening.

That’s right, I forgot to tell you: it’s not a very nice review. In fact, it’s a textbook example of a hatchet job, DFW going to great lengths to demonstrate to the readers of Science what a ridiculously bad writer Full o’ Bull is, in every possible way.

In the same article, he goes on to review another mathematical novel, Uncle Petros and Goldbach’s Conjecture, by Apostolos Doxiadis, explaining that it, too, was pretty bad, though not as awful as The Wild Numbers.

That wasn’t the only juicy bit of information Linda found. Three years after trashing Full o’ Bull’s novel in Science, DFW’s own book on mathematics came out, entitled Everything and More: A Compact History of Infinity. Aha, the plot thickens!

Right around its date of publication, in October 2003, an interview with DFW appeared in the Boston Globe, in which the “two dreadful books” that he reviewed for Science are mentioned in passing, though not by name, sparing Full o’ Bull and that other guy further humiliation.

Or so it would seem. A few years after his death, his interviewer Caleb Crain, who regularly reviews books for The New Yorker and has written a few novels of his own, posted an audio recording of the entire conversation he had with DFW on his blog.

Linda’s great. She sat through more than an hour of intense mathematical and philosophical discussions to extract a grand total of forty-five seconds that she thought might be of interest to me. Talk about dedication!

In those forty-five seconds, you can actually hear the great DFW deriding Full o’ Bull’s book. How cool is that!

“To hell with social distancing,” I texted Linda. “You’re getting a trans-Atlantic hug for this!”

And so, while Full o’Bull went on turning the crank of his pasta maker, I held my phone up and said: “Hey, have you heard this?”

Before I tell you what happened next, allow me to take you on a little side-trip to Florence, Italy.

It was back in 2019, in early October. On a rare afternoon off from my promotional tour of La Vendetta degli Ottimisti, I had joined the throngs of tourists on the Piazza del something-or-other when I practically bumped into Michelangelo’s David! I had seen pictures of it, but when you see the original statue towering right before your very eyes, holy smokes, it’s awesome.

I stood there for quite some time, marvelling at Michelangelo’s exquisite craftsmanship and having a whole bunch of exalted thoughts about the Italian Renaissance and its crucial role in the history of civilization, meanwhile counting my lucky stars that so many women find self-confidence in a man at least as sexy as physical beauty, because otherwise I wouldn’t stand a chance against dudes like this David.

Turns out I was gawking at a goddam replica the whole time! As my Florentine hosts patiently explained to me over dinner that evening, the original can be admired in a building called the Galleria dell’Accademia, for which you had to make an online reservation weeks in advance. It isn’t often that I feel foolish, but this was one of those occasions.

To spare you guys similar embarrassment, let me tell you right off the bat that the recording you just listened to was a mere replica of the conversation Caleb Crain had with David Foster Wallace.

Although it’s literally what they said, minus a few “uhms” and “you knows”, it’s actually me imitating both their voices.

Disappointed? If you wish to admire the original David Foster Wallace in his full splendor, you are welcome to visit Caleb Crain’s blog at https://steamthing.com/2013/07/audio-files-of-my-2003-interview-with-david-foster-wallace.html. Once you’re inside, Caleb will be delighted to provide you with a link to his own Galleria dell’Accademia, so to speak.

The reason I fobbed you off with a replica (after treating Full o’ Bull to the real thing, mind you) was the following note on the blog: “Please feel free to listen to the audio files and to download them for personal use or personal archiving, but please don’t post them on Youtube or anywhere else online. Thanks!”

No problem, Caleb! It was awfully generous of you to share your precious recording with us, and it’s only natural for you to be protective of its content. We respect that.

I hope that you in turn will appreciate the tender loving care that went into producing this humble replica of your conversation with the great David. Though obviously falling short of the original, my intentions were noble: to offer a wider audience at least an impression, not just of the famous writer’s eloquence and wit, but also of your own breathless eagerness to follow his lead in appraising the two books under consideration, accentuated all the more by your disarmingly frank admission to not having read either one of them yourself. Where in these cynical times do we encounter such unconditional loyalty, such selfless devotion?

As it turned out, Full o’ Bull was already familiar with the excerpt. Maybe that was why he wasn’t amused.

“So you dug up Wallace’s quip about my kindness to animals, eh, Toby? What do you want me to do now: get so flustered that I tangle up my tagliatelle, to the delight of your forty-thousand readers?”

“It’s closer to fifty-thousand now, Linda was telling me. Quite an audience, in other words. Which got me thinking: maybe you’d like to take this opportunity to respond to DFW’s review.”

“Like I said earlier: I have absolutely nothing to say. Wallace trashed my book. That was twenty years ago. Now he’s dead and I’ve moved on. End of story. So if you don’t mind, I’d like to get this pasta done before it dries out.”

“Sure, thing, Full o’Bull, I’ll leave you to it.”

And so I headed back downstairs.

He wasn’t taking the bait. At least, not yet, for it was clear as day that even after twenty (sic!) years, the review in Science was still bugging the hell out of him, and that he was itching to tell me all about it.

As a provocateur, you sometimes need to be as patient as the wildlife photographer who gets up well before dawn to lie in the wet grass for hours, hoping to catch that one brief glimpse of the rare and elusive blue-horned something-or-other that will earn them a spot in the National Geographic.

While we’re waiting for Full o’ Bull to emerge from the undergrowth and start fulminating in the open space that we’ve provided for him, why don’t I tell you a little bit about the role DFW played in my own development as a writer.

Back in my college days, his magnum opus, the nearly 1100-page Infinite Jest, was one of those novels everybody kept telling me I should read. That can be enough to put some people off a book for good, but being an open-minded kind of guy, I was willing to give it a shot as soon as an opportunity presented itself.

And boy, did that opportunity ever come knocking, when I threw a great big birthday bash that year and no less than three of my friends showed up on my doorstep with the exact same gift. You guessed it: Infinite Jest.

One of the copies went missing that very same night, the thieving guest presumably reasoning that I didn’t need all three. Fair enough.

Then, at around four in the morning, a bunch of people started playing truth or dare, and when one of the guys whose name I can’t remember preferred not to disclose some embarrassing detail about his sex life (or lack thereof), he was challenged to eat as much of Infinite Jest as he could. There went my second copy.

Tearing page after page out of the book, crumpling them up and stuffing them into his mouth, the intrepid bibliophage was greeted to raucous cheers and a bottle of beer every time he swallowed one down. Although it was quite impressive how much of DFW’s novel he did manage to ingest, inevitably, he had to make a dash for the bathroom.

As for my third and final copy, I ended up returning it to its gift wrapping and placing it under the family Christmas tree with my stepfather’s name on it, though not before making a solemn pledge to buy a new copy as soon as an opportunity presented itself.

Toby Quinn and solemn pledges? Strange bedfellows, you might think. And right you are. Oh well, not many people can say they owned three copies of Infinite Jest all at the same time.

While all of this was going on, I was working on my own first novel, which I had decided to call F.U.N. As those of you who have read the book will know, there were plenty of good reasons for choosing that title, but my publisher, editor and I agreed that if it reminded people of Infinite Jest, all the better. Being associated with a cult classic, whether rightly or wrongly, was sure to generate extra publicity.

We got a little more than we bargained for when DFW killed himself just weeks before my F.U.N. was scheduled to hit the market. Oops. Now what? Postpone the launch? Change the title? Tragic though his death might be, we decided to go ahead with my debut as scheduled.

The rest, of course, is history: greeted to rave reviews, F.U.N. made quite a splash and vaulted me to instant stardom. But when the New York Times reviewer suggested that the “sadly missed David Foster Wallace couldn’t have hoped for a more fitting tribute”, his grieving fans were outraged. A fitting tribute? More like a middle finger!

“In comparison to the wealth, depth and complexity of Infinite Jest,” one of them wrote, “F.U.N. is nothing but a trail of slime left behind by an amoeba.” Another fan volunteered to take me out at dawn and shoot me.

But it wasn’t long before my growing fan base began to push back. After the stifling clutter of Infinite Pretension, F.U.N. was like a breath of fresh air. That sort of thing.

Heck, I don’t know. Maybe the Quinnies and the Bandanas should have a tug-of-war some day, to settle the issue once and for all. “Very fine people on both sides,” as Donald Trump would say.

When I sat down to dinner with Full o’ Bull and his wife that evening, after first making sure to compliment the chef extensively on his delicious tagliatelle alle vongole, I broached the delicate topic of the review in Science once more.

“I’m a bit jealous, you know. I wish David Foster Wallace had been around to trash one of my books.”

“Oh yeah? Maybe that’s because you’re a writer who loves to be hated and hates to be loved. Not me.”

“Still, you should give yourself credit for having touched a raw nerve. He didn’t just dislike your book, he needed to stomp on it and squash it under his shoe until it was good and dead. When that wasn’t enough, he had to unzip his fly and piss all over it, pull down his pants and take a crap on it, stick a finger down his throat and…”

“Thank you, Toby. We got the picture.”

“Fifty-thousand readers, Full o’Bull, eager to hear your side of the story. That’s a hell of a platform that I’m offering you.”

“You’re putting me on the spot is more like it.”

“I understand your reluctance. Honestly I do.”

His wife meanwhile was muttering to him in Dutch, saying things like “neat doon”, which I gather means “don’t do it”, and “dee gloatsock” while glancing over at me, which as you may recall from an earlier chapter, translates to “that scrotum”.

Gesturing impatiently to her to stop fussing over him, Full o’ Bull then turned to me.

“Nice try, Toby. But I’m not taking the bait.”

“Up to you, my friend. The offer stands.”

I knew it was only a matter of time now. Ten minutes, as it turned out.

“She’s right you know,” he said, as soon as his wife had gone into the kitchen to load the dishwasher and make coffee. “I can’t win. If I stick to the high road by not commenting on the review, you’ll keep provoking me and report to your readers that I’m still not over it, even after all these years. Hahaha! How hilarious.”

“Then why not take the low road and have some fun?”

“Fun for you, maybe. I’ll just come across as petty and vindictive, especially considering that Wallace is no ordinary critic, but a writer way more famous than me, in fact, a cult hero, worse yet: a dead cult hero.”

“Look. I realize I’m being a ‘gloatsock’ for putting you in this position. And yes, I won’t deny having sensationalist motives for hoping you’ll open up about the damage DFW did to your ego. But look at it from the bright side: even if you convince only one percent of my readers that you have a legitimate case against him, that’s fivehundred people right there. In the good old days before social distancing, that would be a whole auditorium full of supporters!”

“Yay.”

“And two percent would make one-thousand people.”

“Yeah, yeah,” Full o’Bull said, getting up from the table. “I can do the math. Mind if I get something from your room?”

“Go ahead,” I said, trying not to sound too eager.

He was back before I could say David Foster Wallace, with the twenty-year-old issue of Science that I recognized from Linda’s email and a bulky folder full of documentation.

Entering the dining room right behind him was his wife with the coffee. Shaking her head at him and flashing a dark look at me, she withdrew to the adjoining living room to watch the eight o’clock news.

“It’s been a while,” he claimed, making a show of having to leaf back and forth through the magazine to find the right page. “Ah. Here it is.”

Folding my hands behind my head, I leaned back in my chair, ready to enjoy the show.

“Besides trashing my book,” Full o’ Bull began his story, “Wallace spends an awful lot of time bragging to us about his knowledge of higher math. In one footnote, he wonders whether he needs to explain a certain mathematical principle to us. In another, he grants us permission to skip over a certain passage if we’re unfamiliar with the math, ‘with no hard feelings on either side’.”

“He’s only trying to be nice,” I suggested.

“Yeah, right. Just like you’re always trying to be nice, eh, Toby?”

“Touché,” I said with a grin.

“Anyways, he now contends that the made-up math in my novel is so silly and nonsensical, that it is clearly not intended to appeal to anyone as well-versed in higher mathematics as he is.”

“Leading him to conclude that your book was written for all of us ordinary mortals,” I filled in.

“That’s right,” Full o’Bull said.

“But then he goes on to say that we won’t enjoy it either, because your characters are two-dimensional, your style stiff and clunky, your English rudimentary at best…”

“Yes, thank you Toby, I’m familiar with the rest of the review. But let’s go back to his main thesis, that the math in The Wild Numbers is too ridiculous to appeal to initiates like him. If so, how come Amir Aczel, a mathematician and popular science writer, endorses my book so enthusiastically on the back cover?”

“Well there you go. Busted!”

“Not so fast. Wallace has an explanation. In a footnote, he writes that Aczel ‘must have been on some euphoriant medication,’ to have enjoyed my novel. Oh, you think that’s funny, do you?”

“Sorry. Go on.”

“No, no, wait. So you think it’s okay for Wallace – a mere amateur mathematician just like me – to question the mental state of a professional mathematician, simply for having a more favorable opinion of my book? In a prestigious periodical like Science?”

“Poetic license, maybe?”

“Oh, c’mon, Toby! He’s scraping the bottom of the barrel here. And quite frankly, I find it appalling that the editors of Science let him get away with it!”

Full o’ Bull was getting a bit red in the face at this point, which became redder still when his wife poked her head around the door to ask him if he could keep it down. She was having trouble following the news.

Whoa. Tension city. For a minute, I was afraid he’d blow up at her. A good thing she didn’t wait around for that to happen, quickly shutting the door and returning to the television.

“And besides,” he now went on with a sigh. “There are two more blurbs on the back cover of my book, from scholars at least as well-versed in mathematics as Amir Aczel. So what was wrong with them? Were they on the same euphoriant medication when enjoying my book? One was Hans Christian von Baeyer, an acclaimed physicist and author of Taming the Atom, and the other…”

Here, Full o’ Bull paused for dramatic effect, looking at me intently.

“… Sir Roger Penrose.”

“Sorry?”

“At the time Wallace wrote his review, Penrose was considered one of the world’s greatest living mathematicians. And even more so today. In fact, just this last October, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his theoretical work on black holes.”

“Oh, okay. I mean: oh, wow! Congratulations, Full o’ Bull!”

“That sure sounds sincere.”

“Look, I hate to be a party pooper, but you won’t believe the number of books I’ve endorsed after just leafing through them, sometimes not even that. Commenting on a certain novel x, I once blurbed: ‘I haven’t laughed this hard since reading y,’ another book I had never looked at, so that technically, I wasn’t even lying.”

“I’m not naive,” Full o’ Bull said, nodding dejectedly. “That possibility did cross my mind.”

“Speaking of naivety, x’s author sent me a really sweet thank-you note. She had been walking on air all week, and if I ever happend to be in the neighborhood, she’d love to treat me to lunch. She was quite a cutie, too, so maybe I’ll take her up on her offer some day. But you never know, Full o’ Bull, maybe this Robert Primrose fellow did actually read your book.”

“Penrose. Roger Penrose.”

“Whatever. What I’m trying to say is that if you want to build a case against DFW, you’re going to need firmer ground than mere blurbs.”

“I know. And there is more.”

“Good! Let’s hear it.”

“Remember this passage, where he quotes my main character’s definition of wild numbers?”

“I must have skipped that bit,” I said, glancing at the spot on the page he was pointing to. “I’m one of those people who phase out as soon as they see numbers.”

“Don’t worry. I’ll spare you the details. But do you see Wallace’s interjections in square brackets? These first two are meant to suggest that my terminology is faulty or even incorrect, while this ‘huh?’ over here indicates that I have stopped making sense altogether.”

“Oh well. You can’t fool a genius, I guess.”

“Maybe not. But how strange, then, that this very passage caught the attention of a number of mathematicians, who, unlike Wallace, had no trouble whatsoever making sense of the definition. In fact, it sparked a lively debate, culminating in my wild numbers being nominated – and accepted – as a new entry in the On-Line Encyclopedia of Integer Sequences!”

“That’s… amazing?”

“Yes, Toby, it was. And for a while, I toyed with the idea of writing Wallace a letter. So my wild numbers were complete gibberish, huh? Too silly to appeal to real mathematicians, huh? Huh?”

“So why didn’t you?”

“Knowing how full of himself he was, I was afraid he would add insult to injury sooner than admit to any wrongdoing.”

“Or not answer you at all. That’s what I usually do.”

“So instead, I took a deep breath and said to myself: you win some, you lose some. Focus on the positive and move on.”

“That’s no fun. But okay.”

“So there I was, being sensible and mature and getting on with my second novel, when: Boom! Wallace’s own book on math appears on the market. So that explained it! Mowing down The Wild Numbers had signaled the start of Operation Everything and More. Shock and awe were needed to stop an evil foreign writer from brutally maltreating mathematics and its practitioners. Indeed, my novel was to be regarded as a weapon of math destruction!”

“Haha! That’s a good one, Full o’ Bull. I like it!”

“Yes, well,” he said, eyeing me suspiciously. “A lot of your fans will be too young to remember this, but Everything and More was written in the same period that George W. Bush and his allies were marching on Baghdad to create what they called a ‘New World Order’. And it was with the same gung-ho rhetoric that Wallace was setting out to create a ‘New Genre’, the right way to write about mathematics, his way!”

“And? Did DFW do as good a job as George W.?”

“Well, do you remember the time president Bush was lowered from a helicopter onto the deck of an aircraft carrier to hold a victory speech before a gathering of cheering marines, with a Mission Accomplished banner as backdrop? Just a few months later, Wallace wowed his fans by planting his literary flag in the realm of mathematics. And on the scene to report on this historic moment was an interviewer from the Boston Globe.”

“Our friend Caleb Crain!”

“The very one. ‘I confess that I myself can’t any longer follow all the math talk in this interview,’ he reminisces on his blog. ‘Even at the time, I was a little out of my depth.’ “

“What charming modesty!”

“The five-star reviews on Amazon.com that I forced myself to read struck a similar tone: much as the readers regretted not having understood more of the book, they saw this as further proof of Wallace’s unfathomable genius.”

“Weren’t there any one-star reviews? They’re way more fun to read.”

“Only a couple. Not enough to console me. Nor to stop Everything and More from selling like hotcakes, as the sales rankings on Amazon.com clearly indicated, much to my chagrin. Don’t do this to yourself, I needed to remind myself. Move on.”

“And so you went back to being a big boy.”

“For the next few months, at least. Until my parents, who as you know live in Toronto, sent me an article from The Globe and Mail, Canada’s leading national newspaper. Entitled ‘When good writers do bad science,’ it was a damning review of Everything and More, written by someone who knew his math. Wallace’s expositions were not only cluttered and confusing, but worse yet, riddled with errors.”

“No kidding!”

“There was only one problem with the review: it was written by Amir Aczel, who might possibly have an axe to grind with Wallace.”

“Or else he forgot to take his euphoriant medication this time.”

“Still, his arguments sounded level-headed and reasonable enough, all the more so when other reviews by math-savvy writers began to appear, signalling the exact same faults with Wallace’s book. The most devastating one of all, entitled ‘Infinite Confusion’, was written by Rudy Rucker, a mathematician and novelist, who… What’s so funny?”

“Caleb Crain, Amir Aczel, Rudy Rucker: what’s with the alliteration, Full o’Bull? You’re not making these people up, are you?”

“Go ahead and Google them, if you don’t believe me,” he said, meanwhile rifling through the folder with documentation.

“Okay, sorry. Go on.”

“Here it is,” he said, triumphantly holding up a page and putting on his reading glasses. “Listen to this:

‘I fully expected to enjoy Everything and More. But it’s a train wreck of a book. A disaster. Nonmathematicians will find Everything and More unreadable, and mathematicians will view it with, at best, sardonic amusement. Crippling errors abound.’

And on it goes from there.”

“Sweet.”

“And the best thing about ‘Infinite Confusion’ is that it appeared in… Science!”

“What goes around, comes around!”

“Exactly.”

“Bravo, Full o’ Bull,” I said, rising from my chair and applauding vigorously. “Bravo!”

“For heaven’s sake, Toby. Cut it out and sit down.”

“Sure thing,” I said. “Still, that was quite a show you just put on.”

“‘Show’ is the right word, I’m afraid. And anyhow, it’s too little, too late. By taking his own life, Wallace not only broke a lot of hearts, but in the shadow of that far greater tragedy, he also robbed me of the opportunity ever to settle scores with him.”

“Hmm. I guess you did take the saying that revenge is best served cold a little too far. And some of my readers may indeed see you as an angry old man beating a dead horse with his cane, if you’ll pardon the expression.”

“Thanks. But yes. My point exactly.”

“Oh well. You’re by no means the only writer I know who can’t handle criticism. If nothing else, you’ve been a good sport by being so willing to show the world what a poor sport you are! That takes guts, too, you know. It really does.”

“Boy Toby, you sure have a way with words.”

“That’s my job.”

Leaning over the table, I patted him on the shoulder.

“Poor old Full o’ Bull,” I chuckled. “Trashed by the great David Foster Wallace, and now stuck with another hotshot American writer. What rotten luck!”

For the first time all evening, he broke into a smile.

“No, Toby. Here’s where you’re wrong,” he said. “I regard your stay with us as an opportunity to do things differently this time.”

“Differently? That sounds a bit ominous. What do you have in mind?”

“I guess you’ll just have to wait and see. More coffee?”

– T. Q.

(coming up next – Chapter 9: My Annus Mirabilis )

‘to do things differently this time’: een spannende wending (en cliff-hanger)!

LikeGeliked door 1 persoon

At the beginning of “Lockdown in Amsterdam”, I worried about TQ’s future. He might be the narrator, but as FoB’s creation, he would get his just desserts. Now, I worry as much about FoB’s future. Is TQ gaining control of his creator?

LikeGeliked door 1 persoon

Ha, ik heb het stuk gevonden! Het leest alsof je het in één ruk geschreven hebt.

LikeGeliked door 1 persoon